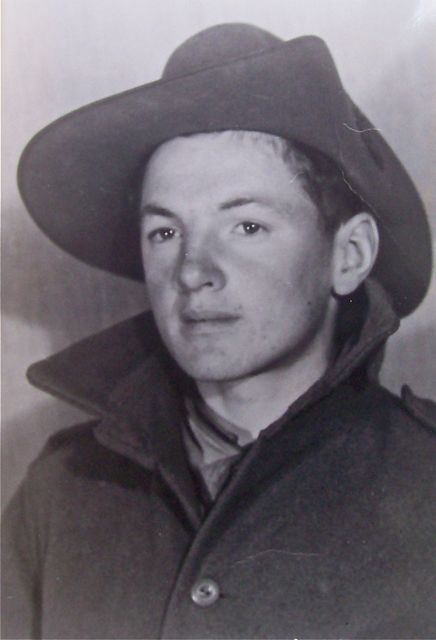

The Story of Billy Young – A Teenager in Changi, Sandakan and Outram Road

Background Notes

I first heard the story of Billy Young from one of his relatives who came to my bookstall on a Sunday morning at Canberra’s Old Bus Depot Market.

I’ve long had a trader’s blood in me. For some years we ran an antique shop in the country, an experience which formed the basis of my first books The Bunburyists, Antique Furniture in Australia andBirdsong. Even now, back in the city, the market stall offers an opportunity not only to escape the desk to meet one’s readers and sign their books, but also to engage in that basic human activity of buying and selling – the foundation of all economic existence.

So it was that Mrs Win Adams came along that September morning in 2006. And after browsing through my military books, she remarked that I should write a book about her husband’s cousin Bill, who’d spent the better part of his teenage years a prisoner of war of the Japanese in Singapore and Borneo.

Cousin Bill

Now, a lot of people say that you should write about their cousin Bill. One of the great joys of the market is to listen to the stories of other people – and even to glean ideas for some future work. Thus, with a writer’s instinct, this cousin Bill stayed in my mind. I had taken Mrs Adams’ phone number fortunately; and almost exactly a year later, nearing the end of writing my book Captain Cook’s Apprentice, it seemed important to locate him.

Following leads from Win Adams I eventually tracked Bill Young to Sydney, and with heart in mouth made the first phone call. It’s always a trepidation. Will the subject respond favourably? Or tell you to go to the devil? Though in this case I needn’t have worried. For the next three-quarters of an hour, Billy regaled me with his stories of growing up around Paddy’s Market during the Depression … of his father who was killed in the Spanish Civil War … of joining the army in 1941 aged only 15 … of Changi – Sandakan – and Outram Road Prison.

Finally, as we ended that first conversation he said, ‘Do you know what the older blokes called me in the prison camp? “Billy the Kid.”’ And I knew I had a book – even a title. For years, as I worked on the book, it was always Billy the Kid. I thought it the perfect name. Only after the manuscript was accepted by Penguin in 2011, did my thinking change. Confronted by commercial realities in this tough time for bookselling, I had to admit that any biography with the title Billy the Kid would most probably end up on the bookshop shelves with the ‘westerns’, among the cowboys and Indians.

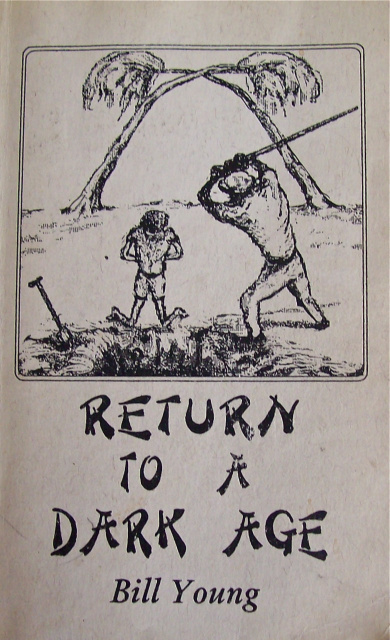

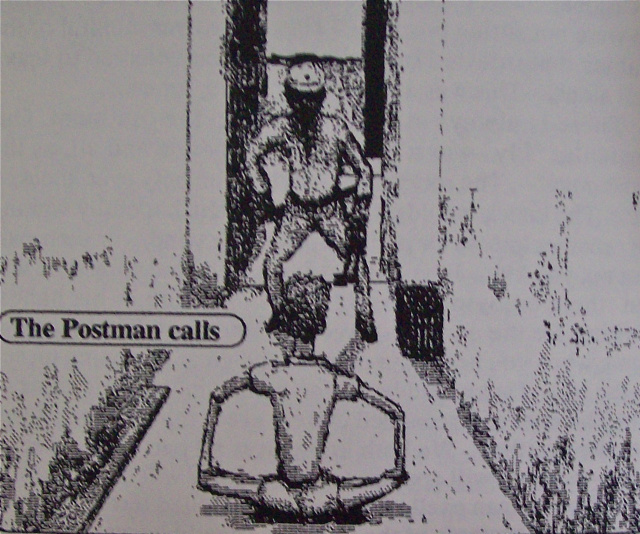

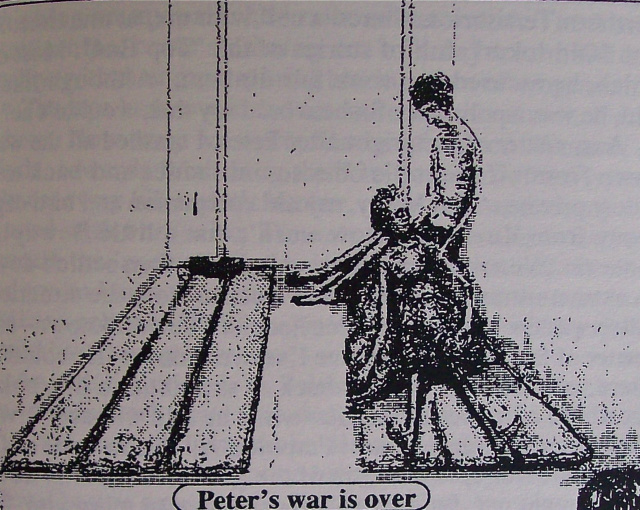

Still, it was as ‘Billy the Kid’ that I did my preliminary reading, especially Bill’s book of his wartime experience Return to a Dark Age. It is raw and it is rough, clearly the work of a self-educated man – like the pictures that illustrate it. But they are powerful; and for all the idiosyncrasies of spelling and grammar, the words conveyed such a remarkable story of adversity and survival that I felt it should be accessible to a wider audience.

More than 60 interviews

I bought a new digital recorder, and in early December went to see Bill Young in his bachelor flat near Kogarah in Sydney … and thus began the first of what turned into more than 60 interviews by phone or face to face… Interviews that spanned many hours over subjects that ranged from Billy’s philosophical views on life and the current issues of the day, to the minutiae of his childhood, enlistment, wartime service, imprisonment, and the painful after-effects on his emotional life as an adult.

I have kept these recordings (apart from several accidental erasures caused by my technological ineptitude), and have made transcripts which I will offer to The Australian War Memorial or the National Library of Australia.

Whatever may be thought of my interpretation in The Story of Billy Young, the material itself offers extraordinarily rich

insights into the lives of working-class Australians in Sydney during the Depression, the factors that led so many underage youths to join up when the Second World War broke out, one rookie’s experience of the fighting on Singapore and subsequent internment at Changi, the Sandakan labour camp in Borneo, and the infamous Outram Road prison. Plus of course the combined effect of all this on his psyche when he returned home in October 1945, not yet aged 20. I feel it should be preserved for future researchers seeking to understand an Australia that, even now, has almost disappeared.

For the thing about Billy is not just that he has lived through these defining events in our 20th century history, but that he is able to recall and recreate them in such vivid and telling detail. He’s a novelist’s dream. I found the men and women he grew up with during the thirties as a kid around Paddy’s Market coming immediately to life again as he spoke of them…

A novelist's dream...

Pop and Ma Jepson, the old circus couple who reared him, keeping a precarious toehold on the ladder of commerce with the market stall and fruit barrows. Millie, their superstitious circus friend. Wingie, the one-arm First World War veteran, who made a bare living selling clothes props, pegs, and skinning rabbits. Billy’s father – Big Bill Young – a drifter, until he was converted to the Communist Party, and became a martyr in the Spanish Civil War…

Here, among the market entrepreneurs, the zealous comrades, coppers, wide-awake boys, school-teachers’ canes, and neighbours struggling to survive poverty and eviction, Billy the Kid discovered that inner resourcefulness and camaraderie that helped him (and so many like him) to endure the horrors of the POW jails. For Billy Young, the Kenpeitai – Nippon’s version of the Gestapo – were just more virulent forms of school inspectors.

Billy’s memory is not merely a colourful one. Where I could check it against a written record, I also found it pretty accurate – certainly on events involving himself. An account in the Workers Weekly newspaper of a Christmas party the comrades gave Billy after his father’s death tallied almost exactly with his own recollection. And the poems, scratched on the walls of his prison cell, that he memorised day after day, and which he can still recite, stack up fairly well when you compare Billy’s version to the published work.

From that very first interview, which itself went for more than five hours of recorded conversation, I was struck by the candour with which Bill Young responded to my questions. As our friendship grew during the years that followed, and as we probed ever deeper into a sometimes difficult past, I was very conscious of the trust he was placing in me. I hope I have been able to honour that confidence.

There were very few matters concerning himself that Bill would not discuss openly – including the effect of the war and its trauma on the loss of his sexual drives, which is something that most men would not talk about. ‘I wouldn’t talk about it either, but I’m in my 80s now and I’ve nothing to lose.’ The few times where we did go ‘off the record’ were purely not to hurt the privacy or the sensitivities of other people, among them his family. His own story, however, remains intact.

Turning outwards

It was not just Bill’s candour or ear for a good yarn that impressed me, there was also his spirit of generosity. Where so many ex-prisoners of war have turned inward and sometimes very bitter upon themselves, he has turned outward. The second half of his life, indeed, has been spent largely trying to educate himself, to analyse the world about him, and to understand as best he can the Japanese mind. He has quite a collection of Japanese books, magazines and films, where he tries to find an answer to the question of how it was such a civilised people came to perpetrate the horrors suffered by the POWs and the civil populace of conquered territories during the war.

He has found no definitive response to his question. But when even now some ex-POWs have difficulties coming to terms with Japan, it is the asking that’s the important thing.

It’s not just the enemy mind, but more importantly his own experience that Billy Young has sought to understand and articulate. And this raises the most significant thing that occurred to me at our first meeting, and impressed itself more deeply as time has gone by. Billy the street kid – the ragamuffin market boy who played truant for days, even weeks, at time – was in fact born with the soul of an artist.

From a very young age he responded to singing. As a boy attending his first school concert, Billy may have thought it rather sissy. But the music remained – as it did as a teenage POW in Sandakan when he was talked into joining a camp choir and found he had a decent tenor voice. He still sings, and can still hold a tune.

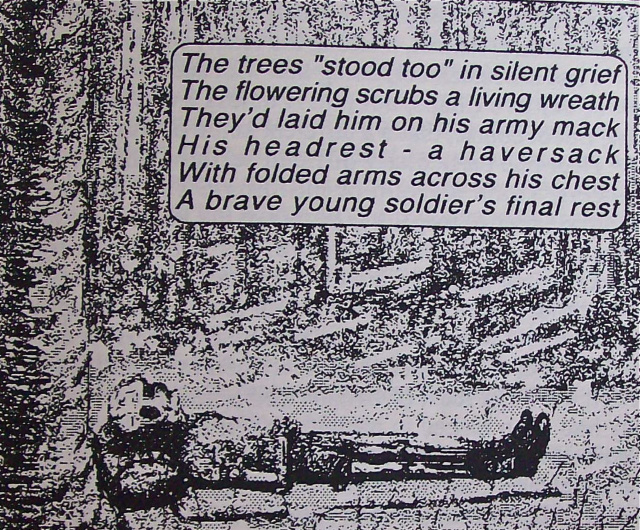

As a prisoner in the stultifying, solitary silence of Outram Road prison, forced to sit cross-legged on a concrete floor all day, he memorised poetry scratched onto the walls by prisoners: verses by Kipling, Thomas Bracken and Robert Service which, as mentioned, he reproduced fairly accurately in his own book. More to the point, Bill began writing his own poems – most poignantly for his 2400 comrades who died at Sandakan or on the three death marches to Ranau in 1945.

Billy's poems

At their best, Billy’s lines touch something quite profound and moving, and I’ve used some of them in the chapter heads to our book.

You cannot tell a battlefield

Once the dead are buried…

That’s not bad. And certainly his poems have charged many an Anzac Day and Sandakan Commemoration Service at home and abroad, as I found when I visited Singapore and Borneo with the historian Lynette Silver and her party for Anzac 2009.

For me, the real purpose of these research trips is to discover the particulars of landscape and atmosphere, so that when I’m writing about a place I can visualise it in my mind and with luck take the reader there with me. This was certainly true of the jungles, campsites, waterways, townscapes and burial sites of Borneo. It wasn’t just colours, textures, sounds and smells. It was the essence of a place, so that at times – and most especially at the Sandakan memorial at dawn on Anzac Day – one could sense the spirits of those murdered POWs passing across what is now hallowed ground.

Something of the same artistic awareness must have seized Bill Young even as an underage soldier during the war. He may not have realised it at the time, but his unconscious mind was storing up images and narratives that would not find their expression for another three or four decades…

The terrors of a night attack at Bukit Timah … the rotting corpse of a soldier laid out in the jungle The flowering scrubs a living wreath … the torture of Jimmy Darlington with sharpened stakes and wet rope under Sandakan’s tropic sun … Billy’s own attempt at escape, capture and interrogation … the glories of a sunset across the water, even as he was sailing to imprisonment … the death of a cellmate, so lightly, alone on his lap …

For years after his return, Bill Young sought to put all those things behind him. It wasn’t until his mid 50s, when his life seemed to be falling apart, that such repressed memories came flooding back into his consciousness. He sought to put them down: at first on paper, as he wrestled with his book Return to a Dark Age – and then, as he taught himself to draw using a computer programme, in paint on hardboard.

Utterly genuine

Whatever else may be thought of them, as I remark in Billy Young, the voice struggling to be heard is utterly genuine, and our emotional response to the scenes that are depicted is deeply felt. I find it fascinating – and strangely reassuring – that a spirit of this artistic sensibility should be found among one who grew up very close to poverty during the depths of the Great Depression. To be sure it is untrained – entirely self-taught. But this in itself is a commentary upon Billy Young’s time and his place in our country’s economic and political history.

For as I go on to observe in our book, ‘... his voice is still able to be heard among those keeping alive memories of Sandakan and Outram Road, when the voices of other veterans are becoming fewer and fainter. Reasserting, for as long as traces of ink may be read upon paper, those bonds that were made among the men of the 2/29th Battalion – the whole 8th Division –in the fires of war, and affirmed throughout their imprisonment.’

All the drawings on this page are from Bill Young's Return to a Dark Age