Finding the right title for your book can be among the most important but elusive aspects of a writer's life. At least it is in my experience, and I often wonder if other authors feel the same?

Sometimes it's easy. A phrase ... an unusual word you come across, may not only trigger the idea for a novel, play or short story, but stay from the outset as the title of the work. I once wrote a novella Spindrift from just such a beginning.

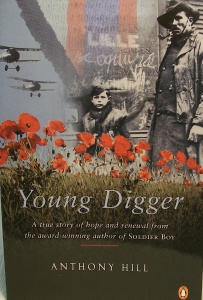

And it's true that a title will occasionally emerge from story as it evolves on the page. A nickname ... a phrase in common parlance used during the writing can suggest itself as a title for the tale. Soldier Boy and Young Digger are two examples from my backlist.

And it's true that a title will occasionally emerge from story as it evolves on the page. A nickname ... a phrase in common parlance used during the writing can suggest itself as a title for the tale. Soldier Boy and Young Digger are two examples from my backlist.

But at other times it can be the very devil to come up with a title that has at once some resonance, market appeal and gives a fair indication of the book's theme.

Some people say that a good title doesn’t matter: that a successful book will make a successful title. Who would have thought, for example, that a play called As You Like It would prove a winner? It might have worked for Shakespeare; but for most of us a good title – like a good cover – is a matter of some significance in a crowded market.

Some years ago, during the writing of a book about Captain James Cook's famous Endeavour voyage of 1768-71, we went almost to the end of production before we found the right title. The story was seen through the eyes of one of the ship's boys, Isaac Manley, who in life rose to become an admiral and was the last survivor of the crew.

Isaac was mentioned in a brief sentence in Beaglehole's biography of Cook, which was the inspiration for the project; but throughout the three years of research, writing and editing I couldn't for the life of me think what to call it. I gave it the working title of Admiral Isaac, though I always knew that wasn't right. It wouldn't generate many sales, and had no obvious connection to Cook, one of the great figures in Australian and Pacific history.

It was only when we were getting ready for the second set of page proofs that a young woman on work experience at Penguin Books suggested Captain Cook's Apprentice – and immediately we knew it was exactly right. It not only gave us the great Captain, but also spoke to the teenage market for whom the book had been written.

It was only when we were getting ready for the second set of page proofs that a young woman on work experience at Penguin Books suggested Captain Cook's Apprentice – and immediately we knew it was exactly right. It not only gave us the great Captain, but also spoke to the teenage market for whom the book had been written.

It's been much the same with the present work in progress – though I'm happy to say I didn't have to wait almost until the death knock. The story is a long saga involving an Australian soldier-settler family spanning two generations: First War – Between the Wars – Second War.

For a long time I called it Aftermath. The word is reasonably good on the ear and tongue; it has a military connotation; and goes to the theme of the book which concerns the long-term effects of the Great War on returned soldiers and their families.

It doesn't exactly grab the imagination however. So for the next draft I called it Sacrifice. Pretty dramatic and relevant. Which I thought to improve by calling it Blood Sacrifice at one point. They'd pick that one up! Until a friend pointed out it sounded like a vampire novel.

Even so, Sacrifice says nothing about the family's love of farming and the countryside, which is such a significant part of the story. Indeed, as their farm was very close to our house, one of the aims has been to express my own love of the land where I live.

Well, I'd just finished the writing when the title came to me. It was there in the last line. The story ends by talking about how much has changed in the landscape. Streets and houses and suburbs now spread across what was once farmland – although the crests of the ridges and surrounding hills have been left much as the soldier-settlers knew them.

And beyond are the enduring mountains. So that not just for this family 'but for all who with love of country lift their gaze it may be said...' and I conclude with a valedictory poem written for prisoners of war thinking on their country and of gum trees nodding under azure skies.*

I looked at the words, and the thought suddenly came. For Love of Country. Of course that's the title! The reason soldiers volunteer for war. It can be found on their gravestones around the world. And in the hearts of those everywhere who remember them. It's also there throughout the story ... but I'd been too blind to see. What do they say about woods and trees...?

The Valley, by Peggy Earl (From The Bunburyists, 1985)

*Line from Vale to the 60 men who died in Naoetsu Camp, by the late Jack Mudie.